|

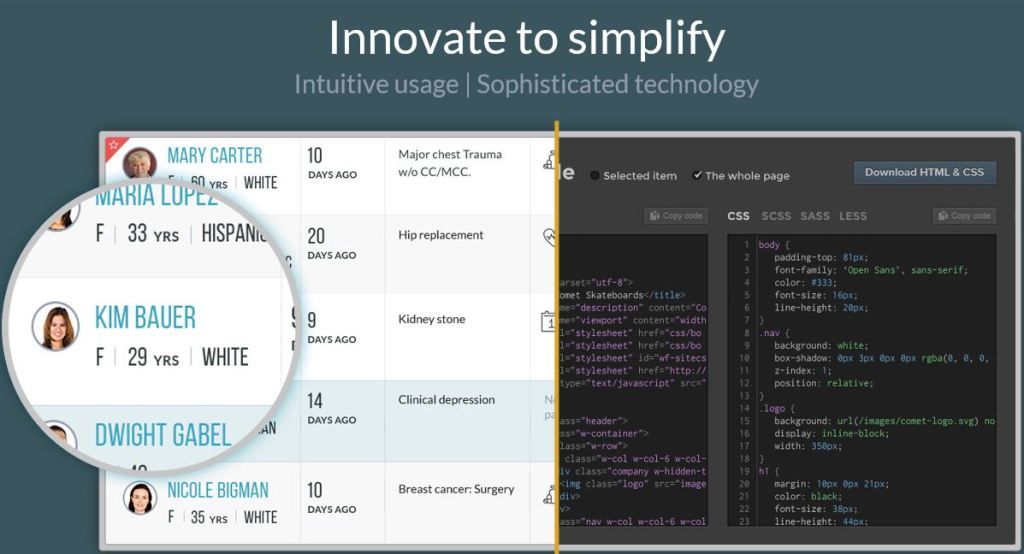

| Something like this? |

After some counseling from the PHB spouse, it came to realize that its wayward tastes in interior design may be a function of going sans helmet during its childhood bicycle riding, its deepening appreciation of bourbon's mysteries and pausing too frequently on Fox News' The Kelly Files.

Naturally, the PHB wants to know the relative influence of each. Increasing exposure will help it propose some ideas for the unfinished basement.

Hospital administrators are dealing with a similar problem when it comes to readmissions.

Approximately 20% of discharged Medicare beneficiaries come back within 30 days. In response, CMS financially penalizes hospitals with high readmission rates for heart attack, heart failure and pneumonia. To reduce that penalty, hospitals have asked about the quality of their care, discharge planning and follow-up outpatient care.

But, what is the relative impact of each? Where should administrators focus their corrective actions?

Or, like the PHB and interior design, are readmissions ominously outside of anyone's control?

According to some interesting research, it turns out that more than half of the variation in readmissions may be outside of hospitals' control. What's worse, CMS doesn't account for that in its calculation of the penalty that uses patient factors, such as age, gender and illness burden.

That's the conclusion of this recent article appearing in HSR Health Services Research.

Herrin and colleagues correlated CMS's Hospital Compare readmission data with each hospital county's socioeconomic data (rural vs. urban, persons living alone, employment status and educational level), access to care (the per capita density of primary care and specialist physicians as well as hospital beds) and nursing home number and quality (the number beds and the number of high-risk, long-term patients with bed sores).

Based on risk-adjusted rates from 4,079 hospitals in 2,254 counties, the authors found that more half of the variation in hospital readmissions was statistically explained by the counties' data. That included persons living alone, low educational attainment, urban setting, a higher number of Medicare beneficiaries, fewer primary care physicians, fewer nursing home beds, higher numbers of nursing home patients with bed sores. More beds and more specialist physicians were also independently associated with higher readmission rates.

The Population Health Blog's take?

As it noted previously, much of the vituperation around the unexplained variation in health care has been less a function of an inefficient health care system and more a function of our inability to identify the underlying drivers of utilization.

And now we're getting better. The HSR article shows that when it comes to readmissions, much of that variation is a reflection of the poverty in our neighbors' homes as well as the strength of the primary care network and the ability of nursing homes to act as a cushion.

Hopefully the mandarins at CMS will take these findings into account as they continue to financially sanction hospitals for readmissions. A more sophisticated approach to risk adjustment could help lessen the budgetary impact of county-level factors that are outside the hospital administrators' control.

And since hospitals' bottom lines typically reflect the populations they serve, better risk adjustment could also lessen the disparate impact on the nation's poorest hospitals.

Image from Wikipedia