Showing posts with label Health Insurance. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Health Insurance. Show all posts

Wednesday, May 25, 2016

Pricing, Product and Audience: Theranos and DTC Blood Testing

In this prior post, the PHB was "long" on Theranos' prospects. Since that was written, Medicare has alleged that a company lab was a "jeopardy to patient health and safety," a peer-reviewed study showed troubling test inaccuracies, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has opened an investigation, higher ups have left the company, years of test results have been "voided" and founder Elizabeth Holmes faces the prospect of a ban from doing business with Medicare and Medicaid. And to add injury to insult, Walgreens has bailed out.

In this well-written Viewpoint published in JAMA, Stanford's John Ionnidis composes a Theranos requiem that ultimately questions the virtues of the company's low-cost and direct-to-consumer blood testing. He argues that while the solution of self-diagnosis and early treatment only sounds revolutionary. That pales in comparison to the far larger problem of misdiagnosis that leads to the reality of overtreatment.

Good point. But, while Theranos' prospects are clouded, the PHB is still long on the underlying three point business model. Theranos got one right, and the other two are within reach.

To wit,

1) The pricing is uncoupled from opaque insurer-based fee schedules and based on rational consumer-driven price points.

2) The product is health insights, not blood testing data.

3) The audience of buyers/regulators need to understand the value-based outcomes

The PHB explains:

1) Theranos stumbles over internal quality control and regulatory compliance issues will play out, and, after a sufficient number of heads roll, will be addressed. Once that's settled, consumer interest in being able to circumvent insurance and "buy" transparently-priced and OTC blood tests should remain considerable. Medicare's fee schedules are ultimately "cost-plus" which includes the costs of a highly inefficient care system. Think about that $500 stitch and it's little wonder why consumers are so willing to forego the sticker-shock and co-pay hassles to beat a retail path to Theranos' door.

2) Consumer insights about screening blood tests come from combining the test results with pre-test odds, sensitivity and specificity. While a smart physician can certainly help patients navigate an abnormal liver function test or a high cholesterol, distance technology combined with consumer-friendly machine intelligence (here's a simple example) can also. It's simply a matter of industrializing and democratizing what we've known for decades. And once consumers can understand tests' imperfections, things will rationally equilibrate between under and overtreatment

3) For many reasons, healthcare is a different business. Among the many reasons for that is that "success" is particularly dependent on the need to understand the short and long term outcomes and costs (i.e. value) of any new care model. That means committing considerable resources to study, document, internalize and publicly report what was achieved at what price. An audience of scientists, regulators, providers, insurers, buyers, politicians, physicians and bloggers want to know: does open-range testing for Hepatitis C paired with education on true and false positive test results reduce the incidence and costs of cirrhosis or liver cancer? Does consumer self-ordering blood glucose levels combined with post-test odds reporting increase awareness of otherwise undiagnosed diabetes and increase claims expense? Does DTC pregnancy testing.... oh, wait, we know that one. You get the picture.

If not Theranos, then some other company will profit from putting patients in at the center of lab testing. The genie is out of the bottle.

Since first posted on May 25, there have been update modifications.

Labels:

DTC lab testing,

Health Insurance,

Medicare,

SEC,

Theranos

Wednesday, November 12, 2014

Rising Healthcare Costs: Delayed or Defeated?

|

| Ready, set...... |

What gives?

While many Obamacare supporters say this is more evidence of Washington's central-planning genius, author Charles Roehrig notes other factors be at play, namely:

1. The 9 million of 2014's newly insured amounts to 3% of the U.S. population. Their baseline spending was probably half of normal, so the resulting increase would expand the nation's spending by a modest additional 1.5%. Since this group is younger, it'll likely be less than that. Their contribution to increasing costs will be harder to detect.

2. What's more, insurance enrollments were finalized relatively late in the year, so these newly insured haven't had much of a chance to give their new benefits an early test-drive.

3. The first quarter of 2014 was an unusually cold winter. The Population Health Blog recalls how freezing temps, wind and snow made for a relaxed day at the clinic. Multiply that across millions of newly as well as long-term insured people, and it adds up.

4. Yes, stupid, it is the economy, which has a strong correlation with healthcare spending. Loss of health insurance thanks to unemployment, declining tax revenues that pressure government insurance programs to limit eligibility as well as benefits, employers' unwillingness to go along with otherwise automatic benefit increases and a general unwillingness of consumers to open their wallets in recessionary times has also added up.

5. Thanks to the expiration of some patents, prescription drug spending moderated.

Bottom line: all of the above are one-time impacts. The economy's impact and new access to insurance are lasting fundamentals that will not go away. It's too soon to tell what is really going on.

The PHB will stay tuned.

Thursday, September 4, 2014

Underwriting vs. Care Management

|

| Rock on, care management |

However, this report on the rise of machines and the continuing displacement of knowledge workers reminded the PHB of the divide between the science and the art in this corner of health care.

According to David Autor, it's only a matter of time until machines begin to displace the high-end brainiacs who oversee the health insurance industry's premium, reserves, claims payments and surpluses. Human judgment will never go away, but logarithmic jumps in processing power combined with the big data that comes from industry consolidation means the "answer" on how much to charge for coverage of a person with diabetes will be less flexible and more preordained.

The PHB, however, is of good cheer.

While underwriting risk will be all about the numbers, managing conditions within those numbers will remain a very individual enterprise. Human needs, preferences, tolerances and culture will continue to shape highly variable decision-making within the care system for years to come. The need for highly skilled knowledge workers who can help patients co-manage their care will grow, not diminish.

Factory farms may be churning out ingredients on an massive scale, but someone has to plate the finished meal.

The music industry may be selling Beyonce at $0.99 a pop, but nothing will replace seeing her live in concert.

Payers and buyers may commoditize cataract care, but someone has to make sure patients take their eye drops.

Underwriting on one side. Care management on the other. The PHB likes where it's at.

Image from Wikipedia

Labels:

Care Management,

Health Insurance,

Machines,

The Economist,

Underwriting

Tuesday, May 6, 2014

Health Insurance Saves Lives? The Story Behind the Story

|

| "Does Romneycare save lives?" |

Yet, research on that topic has been somewhat murky. Most studies have focused on Medicaid as a surrogate for all insurance. Some research suggests that it has no impact on health outcomes, while other studies say it can lead to unnecessary and even dangerous care.

That's why this study that was just published in the Annals of Internal Medicine is important. It says insurance saves lives.

As Population Health Blog readers may recall, Massachusetts required its citizens to buy into "Romneycare" health insurance long before we had even heard of the controversial term "mandate."

Years later, researchers wanted to know if Romneycare - and by implication, its mandate - made any difference in the most important outcome of all: death rates.

The researchers used a "quasi experimental" design that contrasted the county death rates in Massachusetts counties before (2001 through 2005) and after (2007 through 2010) the advent of Romneycare to a set of "propensity matched" counties from New England states that had no health reform.

Mortality data was obtained from the CDC. The analysis was limited to adults aged 20 to 64 years and adjusted for country level age, gender, race, poverty rates, income, baseline mortality rates and unemployment rates.

Results?

During the baseline "before" years, there were no statistically significant differences in mortality between the Massachusetts counties and the control counties. That changed. During the "after" years, mortality, compared to the control counties, statistically significantly declined by 2.9% or by 8.2 persons per 100,000. As further evidence of the impact of insurance reform, elderly populations from the same counties - who presumably had before and after access to Medicare - showed no differences over time.

The paper has a graph that displays mortality rates year after year, and while Massachusetts had a slightly lower (and statistically nonsignificant) baseline mortality rate, there is a small but credible divergence downward over time compared to the control counties.

The Population Health Blog finds the study credible. Propensity matching is the next best thing to a randomized clinical trial, and this study uses a valid concurrent control group to support the notion that health insurance saves lives. Nothing else seems to have accounted for the drop in the death rate.

But.....

1) In clinical medicine, one gauge of treatment effectiveness is "number needed to treat" (or "NNT"). "High value" NNTs range in the 20 to 100 range (i.e., a doctor has to "treat" "100" patients with a particular condition to "cure" one). While every life is precious, Massachusets has taught us that the Romneycare's NNT is 830.* In other words, we have to mandate insurance for over 800 persons to save one life. That's not unreasonable, but after mishaps like this, we should be open to finding better ways to accomplish it.

2) Prior to the institution of Romneycare, Massachusetts maintained a fund that could be used to compensate hospitals for the care of uninsured persons. Since that was a de-facto form of insurance, the Population Health Blog is less confident that the 2.9% difference in mortality rates is a black/white narrative on the transition from "no" insurance to "full" insurance. Rather it's about a transition from one financing mechanism to another. That being said, real insurance would seem to "beat" other forms of health care financing.

3) Can the life-saving track record of a Romneycare mandate be applied to Obamacare's mandate? While there are some important similarities, that doesn't necessarily mean that what works in urban Boston will work in rural Mississippi. More research will be needed, and the Population Health Blog predicts much of it will involve propensity matching.

4) Last but not least, a large part of Romneycare's mandate facilitated the expansion of commercial insurance. This paper doesn't help the Population Health Blog to compare the relative life-saving merits government-run Medicaid vs. a private not-for-profit like Blue Cross Blue Shield. That'll also take more research.

Image from Wikipedia

*An astute reader alerted the PHB that it had initially posted a NNT number spuriously calculated off the 8.2 per 100K difference described above. The authors of the Annals paper correctly give the number as 830.

Labels:

Commercial Insurance,

Health Insurance,

Mandate,

Romneycare

Wednesday, April 30, 2014

Wishful Ideology About Integrated Delivery Systems

Kaiser Health News has posted a telling interview with former White House health adviser Ezekiel Emanuel MD. In it, Dr. Emanuel repeats a bold prediction about the end of health insurance companies:

Kaiser Health News has posted a telling interview with former White House health adviser Ezekiel Emanuel MD. In it, Dr. Emanuel repeats a bold prediction about the end of health insurance companies:Question: You also predict the end of insurance companies as we know them. Rather than continuing to function as the middleman between employers and health care providers, you say insurers may themselves contract with networks of doctors and hospitals, morphing into integrated health care delivery systems. But a one-stop shop isn’t always good for consumers. Networks are restrictive, and at least now, if your insurer turns you down for treatment, your doctor may go to bat for you.

Answer: I don't agree with you. In general, integrated systems do a pretty good job compared to lots of other ways care could be delivered. We like the adversarial system. We believe that’s the best. On the other hand, with integrated networks you can have better coordination of care. And people are mildly sticky. Once you pick an insurance network, you tend to stick with it. That's also good for the insurer. If someone selected you, year in and year out you'll be with them. That changes the dynamic. And to the extent people are long-term keepers, that’s going to be a better arrangement.

"Better arrangement?" The Population Health Blog isn't so sure:

1. As pointed out at the start of the interview, health insurance has been around for more than 200 years. Its staying power is testimony to the enduring value proposition of pooling and monetizing risk. We discard that our peril.

2. Assuming "integrated systems" will competently manage that risk is a stretch.

3. Part of competently managing that risk - even for provider groups - is utilization review. While the interviewer unflatteringly portrays that as "your insurer turns you down for treatment," the truth is far more complicated mix of advantages and disadvantages that have been heavily regulated (an example here) for decades.

4. Can enlightened "coordination of care" make utilization review unnecessary? The luxury of Dr. Emanuel's anti-health insurer ideology makes it easy for him to say yes. So far, inconvenient facts about the ACO pilot program suggest a different story.

5. Plus, can restrictive networks also make utilization review unnecessary? It remains to be seen whether consumers will appreciate the irony that this invention of managed care is now being embraced by Dr. Emanuel and other progressives, or agree that significant limits on provider choice will be a "better arrangement."

6. Last but not least, doctors like the PHB have been trained and acculturated to put the individual patient's interests before any other consideration, including the success of an integrated delivery system. Unable to say no, our loyalty will translate to the usual specialist referrals, sophisticated testing, the latest technology and the priciest drugs. Culture trumps everything.

Like it says, the PHB isn't too sure. Maybe with the right combination of patient incentives, decision support, shared decision making, risk stratification and tailored population health, integrated systems will ultimately prevail. Time will tell.

Give credit, however, to Dr. Emanuel for being consistent over the last two years.

The same is true for the PHB. Based on the emerging facts on the ground, the PHB still thinks the odds remain against Dr. Emanuel.

And the offer of a $1000 bet still stands.

Wednesday, January 15, 2014

One Proposed Measure of Obamacare Success: Drop-Outs from the Bronze and Silver Plans

Naturally, the quizzical Disease Management Care Blog proposes a different metric:

The percent of persons with either 1) "silver" or 2) "bronze" plans who have gone two or more months without paying their insurance premium.

Why, you ask?

1) The silver and bronze plans, because their monthly premium is lower, will attract a disproportionate number of persons who were previously unable to afford health insurance and are now newly insured;

2) According to this just published JAMA article, even if their monthly premiums are fully or partially subsidized, these lower-cost insurance plans cover only up to 60% to 70% of medical expenses. That means cost sharing that can be excess of $6000 and $12,000 for individuals and families, respectively.

As these newly insured persons begin to access health care, high out-of-pocket expenses can lead to two scenarios:

1) Those with subsidized insurance will resent paying anything for a plan that stretches the very definition of "health insurance," or

2) Those with partially subsidized or unsubsidized insurance, because of their mounting bills, won't be able to pay the premium

Either drop-out scenario is very possible. The DMCB isn't aware of any data that describes the normal drop-out rate in low-premium/high out of pocket health insurance plans, but that number exists somewhere. If Obamacare has a higher than expected rate of of drop-outs, that could spell trouble. If the drop-out rate is low, things are going well.

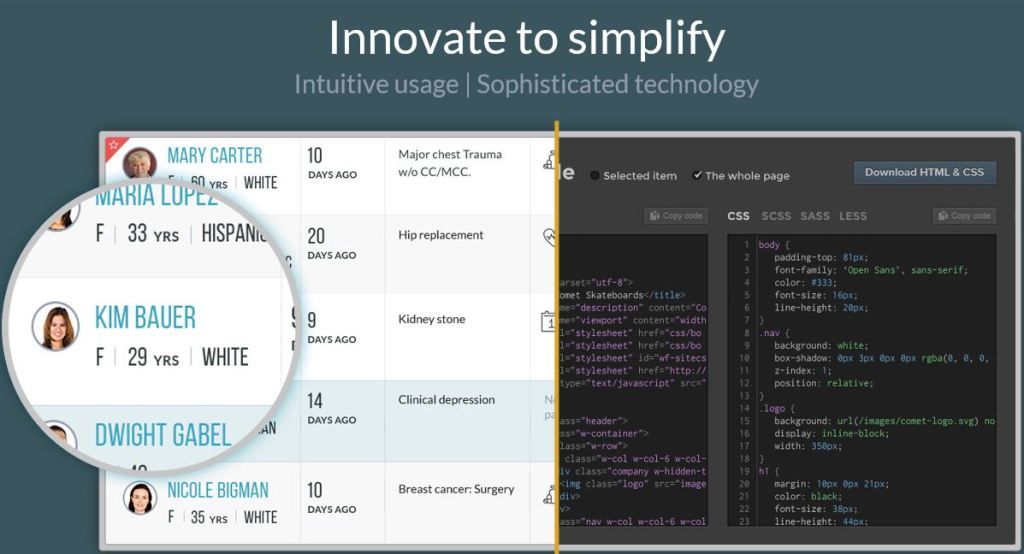

CODA: The image above is an example of an enterprise data dashboard, which is intended to help companies track real time success in achieving specified targets. It's arguably a best management practice and it shouldn't be too much to expect the White House to post an ACA "healthcare" dashboard on their web site. Why not?

Image from Wikipedia

Tuesday, September 10, 2013

How Badly Obamacare Beat Up On the Health Insurers, and What Does It Mean for the Individual Market

|

| D.C. deals with health insurers |

While the White House has been happy to extoll the millions of dollars that were repaid to consumers (even though the individual checks were hardly eye-popping and then there is the risk that they're taxable), the DMCB is interested in what actually happened to the commercial insurers. Did they game the system and garner even higher profits? Or, have they gotten their comeuppance, are now losing money and have to pursue other lines of business, like covering zombie attacks?

This article in the latest Health Affairs looked at that impact of the law when it went into effect on January 1, 2011. The authors used NAIC data to examine the impact on the individual (N=1,219), small group (N=804) and large group market (N=750) insurers.

Individual, small group and large group numbers are broken out below. If there is a *, the change is statistically significant.

In the individual market, from 2010 to 2011:

Median medical expenses, as a percent of premium, increased by 5.5%*.

Administrative expenses, as a percent of premium, decreased by 2.6%*.

Profit (otherwise known as "operating margin" or the bottom line) decreased by 1.3%*. "For profit" insurers fared even worse, with a decline in operating margin of 2.2%* vs. their nonprofit competition with a decline in 0.8%.

2011 operating margins were overall negative:

Individual overall -0.1%.

Nonprofits: -3.5%.

For profits: 0.4%.

In the small group market:

Median medical expenses increased by 0.7%.

Median administrative expenses declined by 1%*.

The bottom line increased by .5%. Nonprofits saw an increase of 1.2%* vs. the for profits having a small decline of .3%.

2011 operating margins were positive, ranging from 2.8% to 3.8% across the non and for profits, respectively.

In the large group market:

Median medical expenses declined by 0.7%.

Median administrative expenses declined by 0.9%%*.

Profit increased by .7%*. Nonprofits saw an increase of 0.1%* vs. the for profits having a increase of 1.2%.

2011 operating margins were positive, ranging from .7% to 2.6% across the non and for profits, respectively.

The DMCB's take:

Obamacare had a single digit impact on health insurers. More was spent on health care and less was spent on administrative costs. While the shifts were relatively small, those changes represent swings of hundreds of millions of dollars to the bottom line in an already thin margin business. If the purpose of Affordable Care Act was to beat up on the health insurers, it was more of a push than a shove.

Small and large group profitability increased and operating margins were positive, while the individual market struggled. As readers may recall, the inability of individuals to obtain coverage at any price was a big factor in the eventual passage of the Affordable care Act. While the future individual market may eventually benefit from an influx of healthy young "invincibles" armed with an accompanying bolus of insurance subsidies, Obamacare ironically hurt the individual market in 2011. If health care utilization didn't go down in 2011 as a result of the economy, it could have been a lot worse.

That tells the DMCB that, contrary to the insurers' reports of doom and gloom, the 80%-85% MLR rule hasn't been a catastrophe. On the other hand, it hasn't been good news for the individual market. If the young invincibles don't 1) respond to the individual mandate, 2) use functioning insurance exchanges and 3) sign up, it could portend further stress on that sector of the health care economy. No wonder the Obama Administration is pushing that so hard.

Wednesday, September 4, 2013

Real News Headline: Improved U.S. Health Care System Saves 28,000 Lives in 2010, Avoidable Death Rate is Decreasing

.jpg) |

| Health reporters at work |

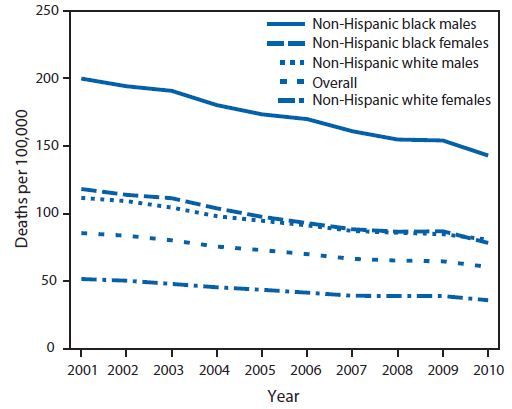

The information reported in the media was taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Sept. 3 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. As the DMCB understands it, the CDC authors pulled 2001-2010 mortality data from the National Vital Statistics System. Once that was done, they counted up the number of persons aged less than 75 years who died of "ischemic heart disease," "cerebrovascular disease," hypertensive disease" or "chronic rheumatic heart disease."

So what did MMWR really say?

The total of "less-than-75" deaths in 2001 was 227,961. For 2010, it was lower at 200,070. Since the population in the U.S. has changed over the last decade, the totals for each of the two comparison years were then expressed as a "per 100,000" statistic.

Since 2001, the "less-than-75" death rate per 100,000 declined by 29%. The decline averaged 3.8% a year.* Persons age 65-74 years had an average decline of 5.1% vs. 3.3% persons between the ages of 55-64.

The good news is that Black (3.9%) and Hispanic (4.5%) persons had greater declines than whites (3.6%). The bad news is that they started and ended with a higher death rate.

Here's a visual display of the data:

The DMCB's take

1. "Avoidable?" The CDC definition implies that perfect control of all cardiac risk factors (for example, cholesterol and weight) for everyone under the age of 75 will result in a 0 per 100,000 cardiovascular death rate. Not so, because those risk classic factors capture some, but not all, persons who succumb to heart attack and stroke.

2. So, this is bad news? "200,000" deaths is an impressive number, but, on an unadjusted basis, that's about 28,000 fewer compared to 10 years ago. Some additional good news is that the U.S. rate of non-fatal heart attack and stroke appears to have dropped significantly also. We are making significant headway in the battle against heart disease.

3. The real story? Persons of color have had the greatest relative benefit but still have the greatest absolute need. That lingering health care disparity went shamefully unmentioned by CNN and was only briefly mentioned by USAToday.

4. Something for everyone: In their "Conclusions and Comments," the authors of the MMWR paper speculated on the benefits of the (still unproven) Million Hearts Initiative (a Berwick-era idea) as well as "health information technology" and various "community prevention strategies" The DMCB's colleagues in the care management service industry will really like the authors' nods toward "team based care" and how "individuals can work toward reducing their own heart disease and stroke risk." If the CDC says so, it must be true - assuming there's a good business model.

5. Speaking of speculation, the authors wondered if the greater decline in the Medicare age group (65-74 years) versus the younger age group (55-64) was because of the presence of health insurance. Maybe, but maybe not. The DMCB also wonders if heart disease is more lethal and less amenable to intervention among younger persons, but can't find any literature to back that up.

6. Politics intrude: Naturally, the scientists who write MMWR are too classy than to curry favor with the appointees that populate the upper echelons of the federal bureaucracy, but that didn't stop the CDC Vital Signs from shamefully putting in a "making it easier for Americans to afford regular preventive health care through the Affordable Care Act" plug. The ACA was not mentioned in the MMWR report because the declines mentioned above occurred in the absence of the ACA.

The DMCB predicts that when the "avoidable" death rate continues to decline by 3.8% in the coming years, Obamacare advocates will take the credit.

*The DMCB isn't sure how 3.8% for 10 years makes for 29% either, but that's statistics for you.

Image from Wikipedia

Monday, July 15, 2013

Commercial Health Insurers Not Only Are Not Going Away, They Shouldn't. Here's Two Reasons Why

|

| Hugging a health insurer |

Answer: liberals only occasionally attack terrorists.

For the latest example of the continuing disdain for health insurers, check out this rather typical July 5 Washington Post article "Is this the end of health insurers?" After extolling one enlightened company's decision to self-insure its workers*, writer Sarah Kliff points out that hospitals can cut out the insurer middle man and offer the same service. The result, says the article, will be the wiser use of the premium dollars, lower costs and fewer coverage denials.

While the physician Disease Management Care Blog agrees that the health insurers' have only themselves to blame for their bad reputation, it doesn't think that these companies are going to go away anytime soon. It's not because, under Obamacare, U.S. citizens are now required to buy their product at any price. It's not because they control hundreds of billions of dollars. And it's not because they've had the ear of the political class for years.

The contrarian DMCB thinks they'll continue to stick around because they perform a two useful public services:

1. Keeping Providers From Going Belly Up: There have been too many examples of hospitals and physician organizations being unable to collect today's premium dollars and hold them as a promise to pay for tomorrow's sickness. Whether it's not charging enough or being unable to say no, providers are vulnerable to running out of cash and being unable to cover their insureds' health care bills. The DMCB says it's better to insulate hospitals and doctors from the perils of the underwriting cycle. Insurers do that.

2. Keeping Providers From Going to the Dark Side: Assuming a hospital or physician organization can hold the dollars, pay for all that health care and end the year in the black, there's a good chance that they'll do it by ultimately employing the same tactics used by many mainstream insurers: denials of services based on determinations of "medical necessity."

*As an aside, self-insured companies don't always act in the their employees best interest. Look at this infamous example and note that Cigna only "administered" the insurance plan on behalf of a self insured organization.

Tuesday, February 26, 2013

The Risk of (Improper) Risk Adjustment: Why The Doctor May See You Now

|

| The stats guys go to work |

As payers increasingly pursue reimbursement strategies that share risk with health care providers, risk adjustment is emerging as an important topic in health policy research. Indeed, for providers, the ability to properly identify the underlying health risks of a specific population could mean the difference between earning savings rather than paying penalties. As the importance of risk adjustment ascends grows, increasing attention is being given to the robustness sophistication of adjustment methodologies. That includes including the data used to estimate the risk of a covered population risk.

In a recent study published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ), John Wennberg and co-authors explore how under-recognized “patient observation bias” can contaminate risk adjustment results.

Previous studies have identified many pitfalls of using observational data as a proxy of a population’s true disease burden. One common example is the phenomenon of “upcoding.” This practice not only adjusts diagnostic codes to maximize reimbursement, it is a well-documented source of bias that spuriously increases variation between geographical regions and complicates risk adjustment.

Wennberg and colleagues show that patient observation bias is another potential pitfall in the science of risk adjustment that has not received such attention. The phenomenon can be quantified by using numerous proxies such as frequency of visits by physicians and the intensity of diagnostic tests (both laboratory and imaging) ordered. Previous research has shown that geographical areas with higher patient observation bias independently correlate with higher rates of comorbidity after being adjusted for all the other relevant patient factors that underlie true risk.

Using a sample of Medicare claims data, the authors computed two different risk adjustment measures: 1) using standard methods; 2) adjusting for potential observation bias. Overall, the adjusted method (using visit intensity) emerged as a more accurate predictor of the population’s underlying burden of illness. Thanks to their ability to identify a source of bias that explained a greater portion of variation in important categories such as sex, age, and race, but was the authors were able, compared to the usual risk adjustment methods, to reduce the variation levels between different geographic regions.

The importance of accurate risk adjustment is not just limited to its potential impact on increasingly high financial stakes in the health care sector. The ability of policy makers to understand why variation occurs in health care costs and utilization across geographical areas has emerged as one of the key questions that may ultimately improve delivery and cut costs in a bloated health care system. This study offers important evidence that part of the answer may indeed lay in the supply-inducing doctors self-referring patients for unnecessary diagnostic procedures that littered Atul Gawande’s account of rising health care costs in McAllen, Texas.

Another important take home lesson, however, also applies: the quality of underlying data. With continued histrionics surrounding access to ever greater amounts of health care data, it helps to remember that qualitatively understanding what one is actually measuring is still as important as the accuracy of the underlying statistical methods.

Labels:

Health Insurance,

Medicare,

Predictive Modeling,

Risk Adjument

Tuesday, January 29, 2013

How Small Business Is Helped By Obamacare... and Large Businesses Will Be Less Able to Compete Against Them

|

| Small business points at its competitor |

Since the DMCB formed it's own corporation more than 5 years ago, it has certainly participated in "protean" business relationships. Once things get underway, the DMCB often discovers that of the many prominent organizations that it does business with really consist of a small core office populated by a few owner-founders, a single administrative aide and one or two payroll folks who oversee the outsourcing of everything else. While the term "protean" is certainly novel, the DMCB thinks distributed, adaptable and organic business networks have been around for years.

But the WSJ editorial opens a window into an underappreciated consequence of Obamacare and the underlying assumptions of the central planners who run Washington DC. The DMCB doesn't necessarily think it's bad, but it sure is interesting.

Read on.

While the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was intended to link employment and health insurance, what it has really done is handed many small nimble interlocked businesses another leg-up against their large traditional mainframe competitors. For example, one colleague pointed out to the DMCB that "new" pharma companies are really marketing departments that outsource manufacturing that, in turn, outsources supply management that outsources I.T. that outsources its cloud services. It's the only way they can compete.

The new economics of health insurance will only accelerate similar trends in other manufacturing and service sectors of the economy. Toss in the ability of people and capital to move and work across borders and the picture becomes even more dynamic. And in the meantime, Washington DC continues to implement the ACA with a legacy of large companies buying comprehensive health insurance for its employees.

Little did anyone anticipate that the ACA would hamper the success of American big business.

Image from Wikipedia

Thursday, September 13, 2012

Bipartisan Health Care Cost Control By Diktat: Insurers or Providers or Both

According to the Kaiser Foundation, health care costs are continuing to go up. Assuming Uncle Sam is doing everything he can to "increase efficiency" and "reduce waste," what are the options that can quickly control costs?

According to the Kaiser Foundation, health care costs are continuing to go up. Assuming Uncle Sam is doing everything he can to "increase efficiency" and "reduce waste," what are the options that can quickly control costs?It's simple: leverage the insurance companies or the providers or both.

1. Tell the insurance companies what they can charge: While the ability of the Feds to regulate insurance remains murky, the Affordable Care Act enables CMS to require that insurance companies "justify" a premium increase of 10% and keep their administrative costs below 15%.

What is less appreciated is that the Medicare premium support plan being championed by Republican Paul Ryan is a variation of this same strategy. Thanks to a voucher that is indexed to the rate of inflation, insurance companies would be essentially told what they can charge for the bulk of their insurance. If the health insurers need to charge more, they'll have to wrestle that out of the beneficiary.

2. Tell the providers what they can charge: For an excellent example of this at the state level, check out this article in JAMA that describes Massachusetts's just-passed law that aims to control the Bay State's $9278 per capita health spending. Large providers (with more than 15,000 patients or $25 million in revenue) are now subject to cost controls that are tied to the state's inflation rate. Enforcement mechanisms will include "performance plan" reviews for violators, public reporting and the threat of civil penalties.

Of course, Medicare's fee schedule functionally dictates what providers can charge for their services at the federal level, but up until now, Congress has been unwilling to leverage that. While a softer and gentler approach of "upside risk arrangements" and "global fees" are being developed, the paranoid DMCB suspects that they'll be ultimately calculated to cover a predetermined charge that is supplemented with a small profit margin.

While Democrats and Republicans have been supportive of a limited number of options ultimately reflecting their ideology, the DMCB predicts that, over time and with a worsening fisc, both parties will converge on using all of the options described above. That's because they'll have no choice.

Heluva way to achieve bipartisanship, but there you go.

Tuesday, August 21, 2012

The "Coporatization" of U.S. Health Care: Why the Good Prognosis for Health Insurers & ACOs May Be Guaranteed

|

| Corporatization |

"Corporatization." It seems this White House likes it.

As the DMCB understands it, this is a policy agenda that favors the formation of huge corporate organizations that dominate the national business climate. Its argument is that, thanks to their size and scope, these gigantic private, public and not-for profit corporations are better able to marshal the resources it takes to launch transformative programs, achieve efficiencies, take risks and make profits that are beyond the normal reach of traditional commerce. Think about the hundreds of billions-of-dollars-approaches to housing, financial services, battery operated cars, high speed rail, solar power, privatized space travel and, last but not least, health care insurance and delivery.

A key ingredient of corporatization is "partnering" with government in a way that blurs the line between private enterprise and the public interest. Ingredients include government-backed financing, special tax breaks, loans, grants, mixed Boards of Directors and sovereign investment funds. The downsides are quite familiar also: crony capitalism and too-big-to-fail status

The best example of corporatization is China. Beijing centrally orchestrates many of its key economic sectors including finance, banking, housing, public transportation and heavy industry with an opaque mix of public and private companies. While political reforms and respect for human rights have been found wanting, the prospect that China could eclipse the United States in the next 25 years has prompted many in the U.S. to admire China and reexamine the merits of old fashioned capitalism and unfettered markets. For an interesting example of that thinking, see this editorial by Andy Stern that recently appeared in the Wall Street Journal.

What could this explain and what are the implications?

1. The abandonment of the government-run "public option" early in the course of creating the Affordable Care Act. Despite his hostile anti-insurer rhetoric, Mr. Obama's ultimate belief in large mega-insurance corporations, a) regulations and b) public subsidies that bind the behemoth insurers to D.C. won the day. And it ain't going away anytime soon.

2. The near ideological support by this Administration for Accountable Care Organizations. Despite little track record that ACOs offer a viable business model, the notion of large regional providers partnering with and led by CMS is fully consistent with a belief in corporatization. This makes the DMCB wonder if Mr. Obama's intent is to assure that ACOs succeed, no matter what.

Sunday, March 11, 2012

Health Care Tithing

As Mr. Romney continues his uninspiring march toward the Republican Presidential nod in Tampa, voters will have a chance to familiarize themselves with the practice of religious "tithing."

If giving up 10% seems like a lot, the Disease Management Care Blog says think again. The concept may not be all that foreign after all, because Americans practically (if unknowingly) already "tithe" to health care.

The amateur economist Disease Management Care Blog cannot resist and naively explores the implications of tithing, beginning with a "thought experiment."

Imagine two neighboring towns. One is populated with persons who earn $50,000 a year. The other has richer persons who earn $100,000 a year. Assume that, for both towns, voluntarily buying comprehensive health insurance costs $10,000 a year (according to the White House, an average premium is $12,680 a year).

Smart DMCB readers know that $50,000 isn't necessarily a lot of money. Persons in that lower income town won't have much left over after they pay for clothing, food, housing, transportation and energy (and in the case of the DMCB spawn, internet access, gaming consoles, tatoos, cable TV and consumer electronics).

Persons in the higher income $100,000 town can afford the basic necessities and more. That means once income passes a certain threshold, the top margin is comparatively more disposable. That makes makes the option of buying expensive health insurance bearable.

In other words, the richer town can effectively "tithe" by devoting a big percent off the top to health insurance and health care. While the cost of clothing, food and housing are elastic, those necessities come first. Health insurance has to wait its turn.

With that in mind, check out the following infamous, public domain and very downloadable graph. No PowerPoint on health care costs is complete without it. While this one is from 2002, the 2006 data can also be easily accessed and aren't much different. While the U.S. is wealthier on a per individual ("capita") GDP ("gross domestic product") basis than the rest of the developed world, it spends far more per individual than would be expected:

Most economists explain that big the gap between the U.S and the other countries represents "waste" from the economic drag of evil insurer-driven administrative costs, unnecessary care in an economically misaligned non-system, an overindulgence in specialists, our love for the latest technology, a widespread belief in taking drugs for every ailment and time wasted reading the DMCB.

All that (except for the DMCB reading) may be true, but the DMCB also wonders if the graph above is a display of a world filled with $50,000 towns and one $100,000 town. The DMCB thinks it's only natural to for a uniquely wealthy country to be willing to spend much of its excess "top" income on health insurance and health care. When that happens, spending will mathematically jump and the U.S. will appear to be a "nonlinear" outlier.

Functionally, that's tithing. The DMCB doesn't think that's unexpected.

Of course, the economics of wealth and health care is more complicated. Wealth not only results in "parallel" increases in spending (allowing the purchase of dried cranberries for tonight's salad or outfitting that man-cave with miniature gargoyle statuary) but "serial" increases that also lead to the purchase of new goods and services like health care. It may not mathematically equate to 10%, but it is still a fraction that is taken off the top.

The U.S. can afford to commit the top margins of its excess income toward health insurance and health care. It's also "all or none," which may also explain some of the non-linear and disproportionate non-linear compared to other countries.

Contrarian economists have been arguing this for years, but the DMCB never heard it described as "tithing." While health insurance has "stolen" income from U.S. employees' paychecks and employers' profits, what's also happened is that that economic damage is partially limited to top "excess" levels (or brackets) of our nation's business and personal income.

You heard the concept of health care tithing here first. That being said, the DMCB can think of some wrinkles:

1. The Fat Lady teaches that humbly religious tithing takes the first 10%, even if there are other necessities. The political version of that in the U.S. is "entitlements."

2. The other "$50,000"countries devote a percent of their budget to health care, but the DMCB thinks that they're buying "preference insensitive" care at the lowest level of service. Thanks to our wealth, the U.S. can technically afford to indulge in preference sensitive care services - and the variation that comes with it.

3. Many persons in the U.S. are very low income and can't afford any care. That's true, but thanks to our GDP, they get the worst of both worlds: they have the appearance of a higher than average income compared to the world without the ability to pay the tithe.

4. Just because we're willing to "tithe" doesn't mean we're getting our money's worth and that there isn't diminishing marginal utility. We aren't and there is.

5. If inflation and stagnant wages are eating away our ability to pay for the more basic necessities, it's easier to stop tithing and jettison health insurance altogether. That means we're less able to cut health care by 10% to make up for a 10% increase in the cost of other goods and services. This may partially explain ....

1) why persons are willing to completely "drop" their health insurance and use 100% of the top marginal money for life's more basic necessities;

2) why employers would be willing to drop health insurance altogether as a benefit. We may be underestimating the likelihood of a flood of persons being pushed into the individual market when the ACA kicks in.

6. Tithing is an expensive proposition. No wonder Professor Fuchs is proposing a simple solution: pay for it all with a VAT.

7. Think the cavernous edifices, expansive lobbies and pricy stonework of premier health care institutions sometimes make them resemble cathedrals? Now you know why.

If giving up 10% seems like a lot, the Disease Management Care Blog says think again. The concept may not be all that foreign after all, because Americans practically (if unknowingly) already "tithe" to health care.

The amateur economist Disease Management Care Blog cannot resist and naively explores the implications of tithing, beginning with a "thought experiment."

Imagine two neighboring towns. One is populated with persons who earn $50,000 a year. The other has richer persons who earn $100,000 a year. Assume that, for both towns, voluntarily buying comprehensive health insurance costs $10,000 a year (according to the White House, an average premium is $12,680 a year).

Smart DMCB readers know that $50,000 isn't necessarily a lot of money. Persons in that lower income town won't have much left over after they pay for clothing, food, housing, transportation and energy (and in the case of the DMCB spawn, internet access, gaming consoles, tatoos, cable TV and consumer electronics).

Persons in the higher income $100,000 town can afford the basic necessities and more. That means once income passes a certain threshold, the top margin is comparatively more disposable. That makes makes the option of buying expensive health insurance bearable.

In other words, the richer town can effectively "tithe" by devoting a big percent off the top to health insurance and health care. While the cost of clothing, food and housing are elastic, those necessities come first. Health insurance has to wait its turn.

With that in mind, check out the following infamous, public domain and very downloadable graph. No PowerPoint on health care costs is complete without it. While this one is from 2002, the 2006 data can also be easily accessed and aren't much different. While the U.S. is wealthier on a per individual ("capita") GDP ("gross domestic product") basis than the rest of the developed world, it spends far more per individual than would be expected:

Most economists explain that big the gap between the U.S and the other countries represents "waste" from the economic drag of evil insurer-driven administrative costs, unnecessary care in an economically misaligned non-system, an overindulgence in specialists, our love for the latest technology, a widespread belief in taking drugs for every ailment and time wasted reading the DMCB.

All that (except for the DMCB reading) may be true, but the DMCB also wonders if the graph above is a display of a world filled with $50,000 towns and one $100,000 town. The DMCB thinks it's only natural to for a uniquely wealthy country to be willing to spend much of its excess "top" income on health insurance and health care. When that happens, spending will mathematically jump and the U.S. will appear to be a "nonlinear" outlier.

Functionally, that's tithing. The DMCB doesn't think that's unexpected.

Of course, the economics of wealth and health care is more complicated. Wealth not only results in "parallel" increases in spending (allowing the purchase of dried cranberries for tonight's salad or outfitting that man-cave with miniature gargoyle statuary) but "serial" increases that also lead to the purchase of new goods and services like health care. It may not mathematically equate to 10%, but it is still a fraction that is taken off the top.

The U.S. can afford to commit the top margins of its excess income toward health insurance and health care. It's also "all or none," which may also explain some of the non-linear and disproportionate non-linear compared to other countries.

Contrarian economists have been arguing this for years, but the DMCB never heard it described as "tithing." While health insurance has "stolen" income from U.S. employees' paychecks and employers' profits, what's also happened is that that economic damage is partially limited to top "excess" levels (or brackets) of our nation's business and personal income.

You heard the concept of health care tithing here first. That being said, the DMCB can think of some wrinkles:

1. The Fat Lady teaches that humbly religious tithing takes the first 10%, even if there are other necessities. The political version of that in the U.S. is "entitlements."

2. The other "$50,000"countries devote a percent of their budget to health care, but the DMCB thinks that they're buying "preference insensitive" care at the lowest level of service. Thanks to our wealth, the U.S. can technically afford to indulge in preference sensitive care services - and the variation that comes with it.

3. Many persons in the U.S. are very low income and can't afford any care. That's true, but thanks to our GDP, they get the worst of both worlds: they have the appearance of a higher than average income compared to the world without the ability to pay the tithe.

4. Just because we're willing to "tithe" doesn't mean we're getting our money's worth and that there isn't diminishing marginal utility. We aren't and there is.

5. If inflation and stagnant wages are eating away our ability to pay for the more basic necessities, it's easier to stop tithing and jettison health insurance altogether. That means we're less able to cut health care by 10% to make up for a 10% increase in the cost of other goods and services. This may partially explain ....

1) why persons are willing to completely "drop" their health insurance and use 100% of the top marginal money for life's more basic necessities;

2) why employers would be willing to drop health insurance altogether as a benefit. We may be underestimating the likelihood of a flood of persons being pushed into the individual market when the ACA kicks in.

6. Tithing is an expensive proposition. No wonder Professor Fuchs is proposing a simple solution: pay for it all with a VAT.

7. Think the cavernous edifices, expansive lobbies and pricy stonework of premier health care institutions sometimes make them resemble cathedrals? Now you know why.

Wednesday, December 7, 2011

Free Drugs For Heart Attack Patients: The Analysis Behind the Analysis of the MI-FREEE Trial

Assuming drugs are not free, should all patients in an insurance plan that covers medications get the same coverage at the same price?

Assuming drugs are not free, should all patients in an insurance plan that covers medications get the same coverage at the same price?While that may seem to be a no-brainer, there's plenty of research (for example) that demonstrates that out-of-pocket costs can reduce persons' willingness to take their pills as prescribed. While that may be the price of doing business, why not give persons who really need a particular life-saving medication a price break? While that may seem unfair, suppose everyone in the risk pool benefits from lower health care costs?

Enter the Post-Myocardial Infarction Free Rx Event and Economic Evaluation (MI FREEE) trial.

Too long to read at one sitting you say? The Disease Management Care Blog at your service!

The study involved Aetna beneficiaries who had just been discharged from a hospital following a heart attack. While the trial was randomized and prospective, the randomization occurred at the level of the insurance plan. Various employer, union, local government or other association groups (and their patients) were randomized to one of two arms:

1) an intervention group where patients had no out of pocket cost sharing or co-pays for brands or generics in four classes of drugs that have been shown (go to page e227) to reduce the risk of death after a heart attack: 1) statins, 2) beta blockers, 3) ACE inhibitors and 4) ARBs, or

2) the usual co-pay for statins, beta blockers, ACEs and ARBs.

2845 persons were placed in the "no-cost" arm of the study and 3010 were in the "usual cost" arm of the study. The mean age was 53 years and 75% were men. About 34% and 27% of both groups had diabetes and heart failure, respectively. Over time, the percent of persons that were fully compliant with their medications became different: 31% in the usual cost vs. 41% in the no-cost group. The median duration of follow-up was 394 days.

And what happened? When the number of first-time fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events were grouped in and counted with heart surgeries (that included angioplasties, stenting or open bypass), there was no statistical difference between the two study arms: 18.8 events per 100 person-years "usual cost" vs. 17.6 per 100 person-years in the "no-cost" group. There was no difference in the cardiovascular death rate either: 2.0 vs. 1.7 deaths per 100 person years.

However, there was some good news. The combined endpoint similarity was largely driven by a high equal number of heart procedures in both groups (which seemed to involve more than 10% of the entire study cohort). If the surgery patients are backed out, there were fewer first time fatal or non-fatal vascular events and strokes in the "no-cost" group.

There is even more good news. Some patients had more than one event (a patient could have a heart attack, a stroke and then open heart surgery, for example). When the total number of events was added up, there was a difference and it was statistically significant: 329 per 100 person-years in the "no-cost" group vs. 406 per 100 person years in the "usual cost" (p=.03).

Did the insurers save any money? Yes and no. Average total spending in the "no-cost" group tallied up to $18,254, while the "usual cost" group averaged $20,238. While that's a $2000 difference per patient, it failed to achieve statistical significance. However, when the DMCB multiplies those savings by the number of persons in the no-cost treatment arm, it calculates $5,690,000 in total savings. That sure sounds financially significant.

DMCB criticisms:

1. Heart procedures - which may be prone to factors other than clinical need - may have diluted the results in this trial, especially if a significant proportion of them were not evidence-based.

2. The secondary prevention benefit of drugs for heart attack patients extends beyond 394 days. If this study had gone longer, the difference may have expanded over time and achieved statistical significance.

3. While a cost difference of $2000 did not reach statistical significance, that may have been because insurance claims follow a non-Gaussian distribution, making their analysis very tricky. In addition, the DMCB thinks that a real world savings potentially exceeding $5 million is very noteworthy.

DMCB questions:

1. It'd be nice to know if patients with a higher burden of disease (for example heart failure or diabetes) and therefore more vulnerable benefited more than persons with less disease burden. If so, would it make sense to limit the "no-cost" option to heart attack patients at the highest level of risk?

2. There is no information on the level of out-of-pocket costs in the usual-pay group. As co-pays increase, medication adherence goes down. We don't know if Aetna's pharmacy benefit is typical of the rest of the market.

DMCB insights:

1. The possibility of $5 million (or more if compliance can be increased beyond 41%) in savings may make paying patients to take their pills seem reasonable. Silly you say? Think again.

2. Since $5 million in cost reductions that can result from just a 10% swing in medication compliance, readers should gain a better appreciation on the stakes behind disease management. If nurses can talk patients into taking their pills, the downstream savings can be potentially huge. And why stop there, why not combine no out-of-pocket costs with disease management?

Summary:

While the authors dutifully report that the primary outcome of the study (the number of first non-fatal or fatal heart attacks or some type of heart procedure) was the same in both groups, the DMCB remains impressed that free drugs for heart attack patients may be worth it and that Oncle Karl may have been right and that the University of Michigan VBID folks are on to something. That's because the total number of events achieved statistical significance and there were some specifics that may have blunted the study's ability to get at the other outcomes.

Image from Wikipedia

Sunday, September 25, 2011

Scrimping On Medical Out-Of-Pocket Expenses While Splurging On Luxury Items

Is it good or bad to ask patients to pay for a portion of their health care with their own money, i.e., "out of pocket?"

Is it good or bad to ask patients to pay for a portion of their health care with their own money, i.e., "out of pocket?"If you think it's good, you probably believe that consumers need to bear some of that cost and that markets can drive wise-decision making. You like to quote the famous RAND study.

If you think it's bad, you probably believe cost-sharing can cause persons to withhold needed care and paradoxically can cause unwise decision making. You probably like to quote studies like this.

Which reminds the Disease Management Care Blog of a patient named Victor (not a real name), who refused to get his yearly diabetic A1c blood test because it was going to cost him $5. He understood the importance of the test but thought the charge was simply too much. The exasperated DMCB knew the guy had a nice car and could afford it. It figured, given a choice between foolish luxury and good health, this patient was being shortsighted.

This behavior isn't unknown to managed care executives, who know that many of their middle class and employed enrollees come from socioeconomic backgrounds that make it very possible to pay five lousy bucks for a blood test. While it's an issue for indigent patients, if well off and rational patients "choose" to not invest in their own health, that's not the fault of the insurer, is it?

Which is why the DMCB found this New York Times article on consumer scrimping and indulging fascinating. In response to our "new economy," Americans are cutting back on common household staples and simultaneously splurging on luxury items. When it comes to items like household cleaners, shampoo and batteries, consumers are squeezing pennies. Yet, the sales of high-end handbags, shoes and watches are going strong.

The conclusion of the Times' article is that the wear and tear of daily sacrifice results in an occasional need to indulge. Maybe persons think they deserve an occasional reward or just get tired of doing with less, but whatever the cause, this has important lessons for the pricing of health insurance deductibles, co-insurance and co-pays:

1) enrollees use completely different standards when it comes to willingness to pay for "necessities" versus paying for "extravagance." If it's a "necessity," patients like Victor will say no if the price point is too high.

2) just because enrollees could economically "afford" a relatively small fee for a medical service doesn't mean they'll perceive that they can afford it. For Victor, $5 was too much.

Make sense? Maybe not to the DMCB, but that's the reality of health care consumerism. Health insurers should pay close attention and wonder if it could be their fault.

Sunday, July 31, 2011

Why U.S. Treasury Ratings Matter To Health Insurers

Even as the Washington D.C suzerains try to demonstrate that they are capable of governance by hammering out a last minute budget compromise deal, there's still a likelihood that U.S. Treasurys could still eventually get "downgraded" by those murky rating agencies.

Even as the Washington D.C suzerains try to demonstrate that they are capable of governance by hammering out a last minute budget compromise deal, there's still a likelihood that U.S. Treasurys could still eventually get "downgraded" by those murky rating agencies. If so, what's the big deal for current Treasury holders? The Administration has made it clear that the nation's creditors will get their interest payments no matter what, even if means withholding payments for the hospitals that are caring for next year's Democratic voters. Interest rates on future Treasurys may go up but that should be tolerable. All is well, right?

Alas, notes the Disease Management Care Blog, it's not so simple. That's because current Treasurys are bought, sold and therefore "priced" in a circulating secondary market. A downgrade would make those existing Treasury's appear more risky, which could drive their secondary market price down.

For commercial insurers, including health insurers, this could turn out to be a big deal. Much to the chagrin of liberal politicians and populists, health insurers need to keep reserves (the money held to pay future obligations) and a surplus (a financial cushion, just in case the reserves fall short). Instead of just putting that all that money in a bank, insurers invest it in interest bearing vehicles and that includes Treasurys. With a downgrade, their price, i.e. value, could go down, which, if pegged at a market price, could make it appear that the insurers' reserves and surplus have suddenly grown smaller.

With an announcement of a downgrade, millions of dollars of insurer money in reserves and surplus could evaporate. That would make it appear they are at greater risk of not being able to meet their obligations.

It gets worse. As Treasury prices go down, other commercial bond prices will follow. Treasurys' lower prices will ironically make the good faith and credit of the U.S. government comparatively more attractive for secondary market investors worldwide. Holders of other types of bonds who want to sell will need to compete by lowering their prices also. As other bonds go down in price, the value of the insurers' investment portfolios will contract further.

And that could mean that health insurers will have less room to move. Since they already are a low margin business (latest number is 4.3%), the DMCB thinks a Treasury downgrade could be one more reason for commerical health insurers to not moderate their prices in the face of relentless health care cost inflation.

The DMCB offers some other asides:

An obviously overnourished New Jersey Governor Christie was recently hospitalized with asthma. It turns out obesity is a distinct risk factor. Hopefully the big man will be recruited into one of the New Jersey State employees' disease management programs (check out page 7 here) that is paired with a weight loss program. In most programs, dealing with co-morbidities is standard fare.

To the non-surprise of family and friends alike, Amy Winehouse died on July 23. Preliminary autopsy findings showed nothing amiss and toxicology is pending. Assuming drugs were somehow involved, its no accident that it occurred at home and on a weekend day, which are a favorite place and time for recreational drug abusers. If it was cocaine, the typical cause of death is cardiac arrest; it's not unusual for autopsies to be normal. if it was ecstasy, the cause of death is delirium followed by cardiovascular collapse.

Thursday, December 2, 2010

Disease Management, ie Population Health Management Organizations (PHMOs): Plan B to Support the Creation of the Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH)

As the Disease Management Care Blog has previously pointed out, there is is a lot that the disease management industry has to offer the Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH). That's why it agrees with this webinar summary that appeared in the latest issue of Population Health Management.

As the Disease Management Care Blog has previously pointed out, there is is a lot that the disease management industry has to offer the Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH). That's why it agrees with this webinar summary that appeared in the latest issue of Population Health Management.In it, Darren Schulte MD of Alere points out that expectations for the PCMH are very high. Its value proposition includes reversing the decay of primary care, meeting the consumerist needs of an aging population, increasing quality and securing additional practice income. A growing body of evidence suggests that the more successful PMCHs have 1) a dedicated non-physician patient coordinator, 2) expanded in-person and virtual patient access, 3) health information technology that includes a functioning registry and point-of-care decision support and 4) increased practice income. Without these key ingredients, PCMHs have an uphill battle managing a population of patients, building a team-based culture and marshaling resources to change patient behavior.

Enter disease management vendors, although Dr. Schulte prefers to use the politically correct term "population health management organizations" (PHMOs) They have decades of experience in patient education, monitoring, self management, treatment adherence and care coordination. Despite physician skepticism and a cultural bias that favors "build" over "buy," he argues that PCMHs may find PHMOs attractive not only because they're speaking the same language, but because their services are "plug n' play" and highly adaptable across a wide variety of small to large settings. All that needs to be worked is out how PHMO support will be paid for so that the PCMH succeeds.

Enter Dr. Greg Sharp of Ideal Family Healthcare in Woodland Park, CO. He notes that health insurers have a key role to play because they're not only providing the additional monthly payments for the PCMH, but they're being called on to support health information technology solutions and provide work-flow consultation services. Since insurers are very involved anyway, he implies that it's not a great leap form them to also facilitate the sponsorship of PHMOs in the PCMH network. Once that happens, he sees few barriers standing in the way of PCMH team members virtually working with remote or in-person PHMO health coaches, accessing the PHMO's registries and relying on PHMO decision support tools.

The acronym addled DCMB likes this description of how insurer sponsored PHMOs can help PCMHs. For a fiduciary and risk-bearing health insurer, the DMCB agrees that the road to patient behavior change, prevention and savings in medical homes may run through disease management. The DMCB suspects many primary care practices won't necessarily want to create (training the non-physicians in behavior change and coaching?) or be able to afford (buying the hardware and programming expertise to create a fully functioning registry?) all the features of a fully transformed PCMH. Calling it "PHMO" instead of using the scorned term "disease management" will also increase its acceptability.

Smart health insurers will recognize that there will be primary care sites that want to go their own way in establishing PCMHs. That's fine. For those primary care sites that may not have the resources or the inclination to build a fully functioning PCMH, bringing in a "population health management organization" vendor is a good Plan B. That disease management Plan B is a rose that by any other name still smells as sweet in the science of increasing quality and optimizing costs.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

_(14753022132).jpg)