|

| From Better to Belly-Up? |

What happens when you assemble a roomful of academic and Washington D.C. policy experts who have already bought into a core set of assumptions about the Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH) and Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs)? Toss in a tape-recording facilitator-consultant and what you'll get is a 48 page impressively titled document called

Better to Best - Value-Driving Elements of the Patient Centered Medical Home and Accountable Care Organizations. The good news is that this is a highly readable, richly quotable and well-referenced "must-read" for ACO wannabes. The bad news is that, while the title is certainly bodacious, the document ignores a host of critically important issues that are falling outside the participants' closed information loop. By recycling and repackaging the same old assumptions and biases, the authors have made

Better to Best necessary reading, but it is far from

sufficient. The paper was sponsored by The Commonwealth Fund, The Darmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice and the

Patient Centered Primary Care Collaborative (PCPCC).

Don't want to deal with 48 pages? Good thing you regularly check the Disease Management Care Blog. Thanks to the DMCB, you don't have to read the entire document to know that it describes a set of conclusions from a choreographed, day-long and invitation-only (but the DMCB is

not bitter) meeting on the role of

PCMHs in

ACOs.

Better to Best looks at four areas:

1) the PCMH promises to increase patient

access thanks to better off-hours, telephonic and electronic access, timely appointments, a personal relationship with a provider and reductions in health care disparities;

2) the PCMH is a key and central ingredient in the creation of a "

medical neighborhood" that, in turn, leads to the high-value coordination of all those specialty, home care, pharmacy, workplace, home and community-based services. Come to think of it, a medical neighborhood and ACO are practically synonymous;

3) the interconnections of

health information technology (HIT) can optimize engagement, coordinated care and support value - assuming "critical gaps" in functionality and meaningful use criteria are overcome;

4) this is going to need

money that could be packaged as some combination of fee-for-service, case management fees, payment for episodes of care or case rates and comprehensive global payments with or without bonuses at the primary care or ACO level.

As you might expect, in addition to cheerleading the merits of transformed primary care and more money, the document is replete with jargon like "policy action items...", "support federal funding..." "involve consumers....." "create measurement sets...." "research collaboratives..." and "align payment models...." It then closes with a set of consensus statements about 1) keeping the focus on Dr. Berwick's cherished

Triple Aim, 2) measurement, 3) payment model change, 4) learning collaboratives and 5) the continuing role of health plans, providers, academics, employers, federal players, consumers and others.

So what does the DMCB think about findings of this medical home

meeting, this transformational

talk-fest, this sagacious summit of the

select?

There were seven shortcomings:

First off, kudos to the rather contrarian leader of the discussion about interconnected HIT. McKesson's David Nace seemed to be refreshingly skeptical about electronic health records and information exchanges. Contrary to the HIT groupies

magical thinking, Dr. Nace pointed out that this technology won't

transform health care, its job is to

enable it. In fact, the

Better to Best document strongly implies that HIT has yet to meet its potential. Dr. Nace sensibly recommends measuring the impact of HIT using yet-to-be-defined metrics, adjusting the "meaningful use" criteria to support the PCMH and aligning the MU measures of HIT with those of the PCMH accreditation organizations. Too bad Dr. Nace doesn't go far enough in worrying that overemphasis on HIT could distract ACOs from the real work ahead.

Speaking of magical thinking, the

Best to Better participants seem to be assuming that the ACO pilots are a just a learning exercise on a success-lined path that is preordained to lead to certain adoption of the PCMH.

They may wish to reconsider their hubris.

Thirdly, aside from some standard clichés familiar to any reader of the

New England Journal or

Health Affairs, there was very little real-world focus on the

patient. Sure, the PCMH, medical neighborhoods and payment reform will benefit patients, but where is mention of the tailored care plans based on the patients' values and preferences that take full advantage of self care, the support of family and the nuturing of community? Where is the shared decision making that -

to paraphrase one extremist - transcends Outcomes Ver. 1.0?

Fourth, the summiteers assume that a "personal physician relationship" combined with better after-hours and remote communication will

increase access, while failing to note that the published literature on the PCMH supports

reductions in the

standard 2200 patient physician panel size (Group Health's PCMH program

reduced physician:patient ratios from 1:2327 to 1:1800, it's

1:1200 at the VA's version of the PCMH and this review quotes an average

22% panel size reduction).

Fifth, there is no recognition of the physician-hospital tension that will certainly underlie ACOs. To be blunt, if the PCMH is the key to ACO success,

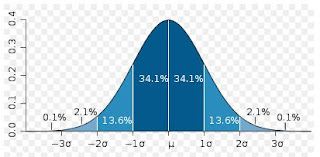

the primary care docs in those PCMHs have to have a meaningful say in day-to-day-operations and be able to direct where the money goes. If the physician-hospital relationships doesn't go well, ACOs will not go from Better to Best but from "Better to Belly-up." 'Nuff said. The image tells it all.

Sixth, speaking of which, who says sufficient numbers of docs

can or, come to think of it,

want to transform their practices into full PCMHs - especially when you read some of the docs comments

at the bottom of this ACO article. To wit: "another flavor of HMO"..."lower provider revenue"...."dubious ethical validity"..." pit the doctor against the interest of the patients"..."black box"... "alphabet soup"..."regional healthcare monopoloy"..."place physicians at the mercy of the hospitals"...."ACOs are more dangerous than HMOs"...."ration care through ACOs." It may be presumptuous to assume that all docs will buy into the notion that a PCMH-ACO is a win-win no-brainer.

Seventh, or last but not least, there is no recognition in

Better to Best of the existence of a

huge group of organizations with two decades of experience in patient education, promoting evidence-based medicine, extending the reach of physicians, mitigating (and accepting) insurance risk, delivering on outcomes-based (including gainshare) performance guarantees and delivering versions of the Triple Aim in commercial and government health insurance programs. While the

Best to Better conference participants have the luxury of their theoretical nostrums PowerPointed in one day meetings, the statutory fact is that ACOs will need to be launched in about

nine months, while it can take "

three to five years" to create a PCMH. As noted previously, there is good evidence (

here,

here and

here) that other care approaches that can be used to support or even backfill the work flows of ACOs without a fully functioning PCMH network.

Bottom line: the DMCB likes the synergies of the PCMH and ACOs and believes that both will be more likely to succeed with each other than alone. That being said, this is no time for wishful thinking. Hard work and significant challenges lie ahead to make this work for physicians AND, most importantly, for their patients.